“A one hundred per cent. record?”

Her shoulders stiffened under her crisp, white blouse as she clenched her teeth. Her patience was starting to wane.

“People move to Sentor because of our excellent care solutions.” Her voice clipped the ends of the words. I felt relief as the visceral scream of frustration escaped from me. It didn’t feel like my voice. Conversations stopped. All I could hear was the huge plastic “Sentor Cares” banner flapping against the concrete outside and the quick muffle-thud beat of my heart in my ears.

“Sentor has the second highest resident satisfaction rate in the North-West.”

I felt like I was at the end of a news item, where the minister trots out a one-liner. Argument is shut down. I stared frostily. People tutted. The murmur of conversation and fingertip tapping on keyboards resumed.

“I can run a balance test.”

I nodded, my throat burning with anger or shame or both.

“There are exceptions. Are you under 25, in full time training or education?” Her eyes didn’t move from the screen.

“You know I’m not. You have my birth-date.”

She didn’t react.

“Do you fall within any of the following exempt categories?” She turned the screen to face me. Employer of more than 200 people, genetic editor, super-programmer, advanced crop innovation. The list was as short as it was ridiculous. “I’ll tick no.” She clicked another box. “The care for you and your child at birth was excellent.”

“It was, I…”

“And you received immediate, intensive healthcare after your no-fault accident.”

“Yes, but it wasn’t no fault, it…”

“The Routemaster-AI has a perfect safety record.”

“Well obviously not…”

“The official report into your accident attributes blame to you.”

“I was unconscious. They didn’t ask me. I can’t access my bank account. I’m locked out of my home. I need to find somewhere to sleep tonight.”

“Is this your signature on the accident report?”

“Yes, but I don’t remember…”

“So, running a balance test, you have benefitted from a state education, further education, immunisations for you and your child, emergency healthcare including…” she scrolled down… “birthing and, most recently, an individual private parent and child room and next of kin state burial… And you were previously working as a laboratory assistant in North-West State Secondary 12 and had done for…” I don’t know whether she paused to check or for effect, the impression of disdain was the same, “eight years, which means that, if anything, you are in state balance deficit.”

“I paid my tax and my national insurance.”

“I have no doubt that you did, it’s just that…” she rolled a few words around her mouth, trying them out, “you weren’t very far along in your working life before reliance circumstances arose.”

“Reliance circumstances! My husband was killed. I was severely injured. I’ve been in hospital for two and a half months, as has my baby. You’ve repossessed my home, my car. I’ve lost my job. What am I supposed to do? You have everything. You owe me now. I’ll, I’ll go to the papers…” I spluttered, “I’ll take this to my MP…”

“There is no representation without taxation. Perhaps you would like to file an anomaly report with the Care Solutions Ombudsman? Sentor takes its civic duty very seriously.”

“I have paid tax all my working life.”

“I think we’ve established that you’ve not paid nearly enough. To gain credit and level 1 entry housing entitlement you will need to re-establish a work hours surplus.” The words registered like hammer blows.

“How am I supposed to do that? My husband and I shared childcare. I can’t do that now. I can’t afford a nursery.”

“You have no relatives who can help you?” she quizzed.

“I don’t know where they are. They left over twenty years ago in the 2042 exodus.”

“Most found the one-time exceptional elderly care payment very liberating. It gave the senior members of our society control over their own destinies. There was a 64 per cent. approval rate.”

“I didn’t vote for it.”

“The majority did. It freed everyone. Win-win.”

“I was too young. I didn’t have a vote.”

“You are free from the care costs of your elderly relatives, something that would weigh heavily in your state balance test. As part of our reboot, restart, reskill programme, you are entitled, even with your deficit, to entry level state nursery and state accommodation.” She handed me raffle tickets from two giant reels, one orange, one blue. “These entitle you to your first night and two hot meals at North-West Region Multi-care Centre 5. You can go now to settle yourselves in. Childcare is for forty-eight hours dependent on your mandatory return and registration back here tomorrow morning when we can discuss the reboot phase of your personalised plan.” She held out the tickets as if they were some sort of prize.

“You need to think of your child.” The words were hard to hear.

“Her name’s Pearl.” She didn’t look up…

“I don’t want to go there.” I knew the place. Back along the Parkway, hunched against the concrete sweep of the

raised dual carriageway, multi-sports hall sized and municipal.

“Her name’s Pearl.” I held on tight and the nursery receptionist half-heaved, half wrestled her out of my arms.

Pearl started to grumble and cry.

“Hello, three-seven-six-three.” The nursery receptionist cradled her softly against her chest, handed back the ticket stub, smiled cheerily and turned on her heel. “Three-seven-six-three…” her voice blended with the hubbub and screams behind the primary plastic panelling that shielded the cavernous childcare facility.

My own voice caught in my throat like split wood. “Her name’s Pearl.”

There were hostel rooms. I was too late to secure an all-women’s room and so I crept into the thick, hot fug and sweat-stench blackness. Crouched up on a camp bed, I wrapped the scratchy, grey blanket around me. My eyesadjusted and searched for shapes. I was liminal now. I, we, existed only in the half light.

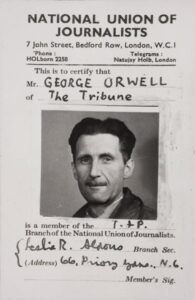

Rosie Lewis was a junior Orwell Youth Prize Runner Up in 2019, responding to the theme ‘A Fair Society?’ We asked Rosie some questions about her inspiration and why she writes:

What was the inspiration behind your piece?

My piece was inspired by the growing political uncertainty that we face in the UK today. I wanted to explore the idea of someone falling through the safety net that is provided by the UK’s welfare state whilst encompassing other futuristic ideas into the piece. The looming election and Brexit deadlines helped me to think about a divided, judgemental, poorly resourced, post-Brexit society, but I also wanted to explore the idea of China’s social credit score (a system where people are awarded a score depending on their behaviour). Overall, I was inspired by current news stories, which helped me to create a futuristic world that could still be understood by today’s audience.

Why did you pick the form you did?

I chose to write a short story in order to display my answer as I thought that following a single character’s struggle and frustration would be the most effective way to communicate my ideas to the reader within the tight word limit. As well as writing a story to be read for enjoyment, I also wanted to subtly highlight that the individualist society that we live in has, and will always have, flaws. I felt like this message was best conveyed in the form of a story.

Why I write:

I started writing in order to express my ideas in a form that could be communicated to, and shared with, others, whether it was a poem or short story. More recently, I have started to write in order to articulate and share my views (whether they are about politics or major issues in the world right now).

Advice to fellow young writers:

I would say that you should write about issues that you are passionate about as you will find it a lot easier to express your emotions through your writing if you are writing about something you actually care about. Also, I would encourage others to try different styles of writing (i.e poems, plays etc.), so that they can find a style they really enjoy.

Influences:

A piece of writing/poem/novel/article film that has influenced me is George Orwell’s 1984. It definitely fuelled my passion for more dystopian and futuristic pieces of writing and also provoked me into questioning our society and whether the decisions our society makes are morally correct.