‘War, Words and Reason: Orwell and Thomas Merton on the Crises of Language’

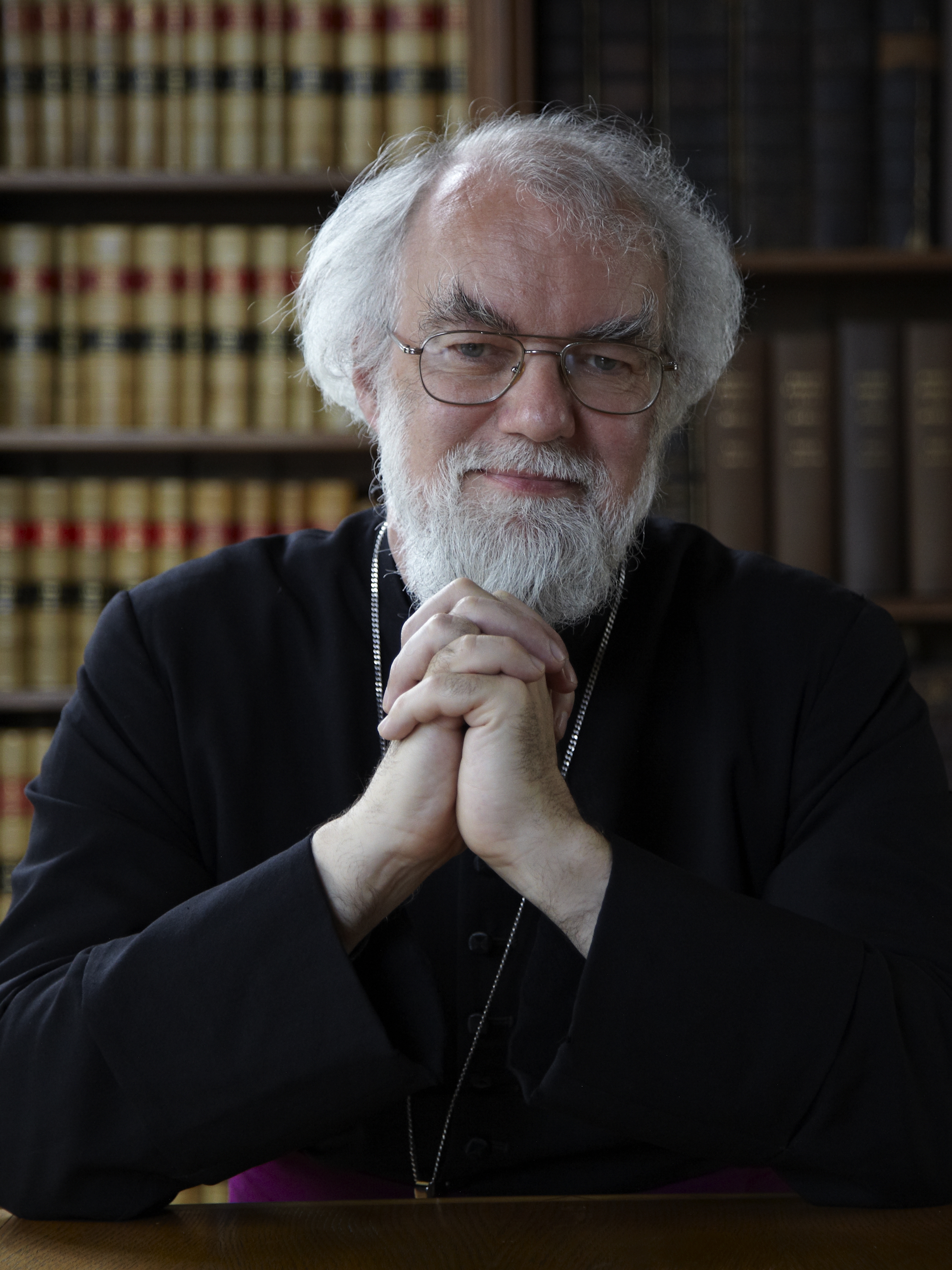

Dr. Rowan Williams

At first sight, it seems hard to imagine a more unlikely pairing than the one announced in this lecture’s title. George Orwell had a profound dislike of Roman Catholic writers (though – as we shall see later – he accorded a grudging respect to Evelyn Waugh as a literary craftsman), and, had he encountered Thomas Merton – especially the earlier Merton – he would undoubtedly have recoiled. Not that Merton was exactly a conventional religious writer. He became a Catholic in 1938 after a distinctly rackety youth, and spent most of the rest of his life as a Trappist monk in the Unites States. But he wrote copiously, corresponding with a wide range of literary figures, including Henry Miller, James Baldwin, Czeslaw Milosz, Boris Pasternak and several Latin American poets, some of whose work he also translated; another surprising friend was Joan Baez. He left behind him, in addition to a huge amount of journal material and many books on prayer and monasticism, a couple of incomplete drafts for novels and a fair quantity of poetry, published and unpublished, some of it dramatically ‘experimental’ in style. This year is the centenary of his birth, and the worldwide interest in his work shows no sign at all of decreasing: some 500 people attended the centenary conference about him in Kentucky this last June. Yet when all’s said and done, he is not on the face of things a natural partner for Orwell, despite his literary contacts and concerns: he remains a wholly committed catholic Christian, and in his first published works he is, for all his extensive literary culture, often dogmatically partisan in his dismissal of all that lies outside the Catholic sphere.

He moved a fair way from this over the years; by the mid 1960’s, he was vocal in his criticisms of the Vietnam war, of the stockpiling of nuclear arms, and of racial segregation and injustice in the USA. His correspondents now included not only poets and novelists, but peace activists and Catholic radicals like Daniel Berrigan and Dorothy Day, as well as a growing number of Buddhist and Muslim friends. But what is most interesting for our purposes is that a central element in his critique of militarism was a stinging analysis of the language of war and weaponry. And this is where the conversation with Orwell might begin (it’s worth noting in passing that he did not read Orwell’s ‘Politics and the English Language’ until August 1967; he admired it greatly – but interestingly his first reaction is to apply it to his own more ‘official’ writing commissions). Earlier in 1967, he published an essay on ‘War and the Crisis of Language’, in which he develops a distinctly Orwellian polemic against the corruption of writing itself by certain aspects of modernity. Beginning with the language of advertising (‘endowed with a finality so inviolable that it is beyond debate and beyond reason’), he works through the implications of this linguistic world in which breakfast cereals, cars and cosmetics are spoken of in the language of theology and metaphysics towards a discussion of the idiom of military planning – ‘as esoteric, as self-enclosed, as tautologous as the advertisement we have just discussed.’ The speech of strategists and of politicians talking about military strategy is characterised by a narcissistic finality. There can be no real reply to the careful and reasonable calculation of the balance of mass killing in a nuclear war, because everything is so organised that you are persuaded not to notice what it is you are talking about. And when that happens, you cannot intelligently converse or argue: all there is is the definitive language imposed by those who have power. It is a natural extension of the language habitually used to describe the processes of other kinds of war. Merton relished the comment of an American commander in Vietnam: ‘In order to save the village, it became necessary to destroy it’, and memorably summed up the philosophy of many supporters of the Vietnam intervention:

‘The Asian whose future we are about to decide is either a bad guy or a good guy. If he is a bad guy, he obviously has to be killed. If he is a good guy, he is on our side and he ought to be ready to die for freedom. We will provide an opportunity for him to do so: we will kill him to prevent him falling under the tyranny of a demonic enemy.’

The main point in all this is that creating a language which cannot be checked by or against any recognisable reality is the ultimate mark of power. The trouble with what Merton characterises as ‘double-talk, tautology, ambiguous cliché, self-righteous and doctrinaire pomposity and pseudoscientific jargon’ is not just an aesthetic problem. It renders dialogue impossible; and rendering dialogue impossible is the ultimately desirable goal for those who want to exercise absolute power. Merton was deeply struck by the accounts of the trial of Adolf Eichmann, and by Hannah Arendt’s discussions of the ‘banality’ of evil. The staggeringly trivial and contentless remarks of Eichmann at his trial and before his execution ought to frighten us, says Merton, because they are the utterance of the void: the speech of a man accustomed to power without the need to communicate or learn or imagine anything. And that is why Merton insists that knowing how to write is essential to honest political engagement. In an essay – significantly – on Camus, whom he, like Orwell, admired greatly, Merton says that the writer’s task ‘is not suddenly to burst out into the dazzle of utter unadulterated truth but laboriously to reshape an accurate and honest language that will permit communication…instead of multiplying a Babel of esoteric and technical tongues.’ Against the language of power, which seeks to establish a sort of perfect self-referentiality, the writer opposes a language of ‘laborious’ honesty. Instead of public speech being the long echo of absolute and unchallengeable definitions supplied by authority – definitions that tell you once and for all how to understand the world’s phenomena – the good writer attempts to speak in a way that is open to the potential challenge of a reality she or he does not own and control. When the military commander speaks of destroying a village to save it, the writer’s job is to speak of the specific lives ended in agony. When the agents of Islamist terror call suicide bombers ‘martyrs’, the writer’s job is to direct attention to the baby, the Muslim grandmother, the Jewish aid worker, the young architect, the Christian nurse or taxi-driver whose death has been triumphantly scooped up into the glory of the killer’s self-inflicted death. When – as it was a couple of months ago – the talk is of hordes and swarms of aliens invading our shores, the writer’s task is to focus on the corpse of a four year old boy on the shore; to the great credit of many in the British media, there were writers (and cartoonists and photographers too) who rose to that task.

Merton is concerned about what happens to our idea of ‘rationality’ in all this. He observes drily that when we express our concern about nuclear armaments falling into the hands of ‘irrational’ agents who cannot be trusted, the implication is that we are the ones who exemplify sanity; so that if and when nuclear armaments are used, we can be reassured that the decision will have been a reasonable one. Slightly cold comfort, as he says. But this is only the most extreme version of the logic of all violent conflict. In another essay on war, Merton argues that it is not really true that war happens when reasoned argument breaks down; it is more that ‘reason’ has been used in such a way that it subtly and inevitably moves us towards war. In one sense Clausewitz was right: war is the continuation of diplomacy by other means. The rationality which increasingly asserts that only our position is sane necessarily defines the opponent as lacking reason and thus lacking ‘proper’ language. We don’t need to talk to them; which means that we don’t ultimately share a world with them; which means that their death is not an issue for us. ‘Listening is obsolete. So is silence. Each one travels alone in a small blue capsule of indignation’ (another text from 1967).

In the summer of 2014, I visited South Sudan to find out more about a number of local development projects supported by Christian Aid. The horror that had been experienced in the preceding months as the country descended into civil war was appalling enough (thank God that at last the media here is beginning to attend). But for me the revelatory moment was realising that the conflict between the two factions in the country was not ‘about’ anything: it was a matter of sheer personal rivalry and power lust (as well as ordinary greed). Those who had attended the peace talks in Addis Ababa confirmed that there was in a way nothing to talk about, nothing to negotiate; the only agenda was who would prevail, and considerations of the good of Sudanese society had no traction whatsoever. Each side travelled alone. Each gratefully assimilated the atrocities of the other side as justification for their own. Rationality had shrunk to the size of a pair of egos wholly detached from any other reality; Merton’s diagnosis seemed (and seems) exactly apt.

Readers of Orwell will by now have felt, I imagine, more than a flicker of recognition. The great 1946 essay on ‘Politics and the English Language’, along with several of the pieces Orwell was writing in his last years, is not about the aesthetics of writing, as the title makes plain – though it has often been used simply to make a point about the decline of the language. Orwell is clear that linguistic degeneration is both the product and the generator of economic and political decadence. And if so, the critique of this degeneration is not a matter of ‘sentimental archaism’ but an urgent political affair. Like Merton, he identifies the stipulative definition as one of the main culprits: a word that ought to be descriptive, and so discussable, comes to be used evaluatively. ‘Fascism’ means ‘politics I/we don’t like’; ‘democracy’ means ‘politics I/we do like’. ‘Consequently the defenders of every kind of regime claim that it is a democracy, and fear that they might have to stop using the word if it were tied down to any one meaning.’ Bad enough (and interestingly there is a not very well-known essay of 1944 by C.S. Lewis making the same general point); but this is really just a symptom of a deeper malaise. Vagueness, mixed metaphor, ready-made phrases, ‘gumming together long strips of words’, pseudo-technical language are ways of avoiding communication. And those whose interest is in avoiding communication are those who do not want to be replied to or argued with. This sort of language aims to make us ignore the reality that lies in front of it and us. ‘People are imprisoned for years without trial or shot in the back of the neck or sent to die of scurvy in Arctic labour camps; this is called elimination of unreliable elements.’ Just as for Merton, the lethal danger in prospect is a form of speech that silences the imagination of what words truly refer to. It denies the shared world in the name of a world controlled by self-referential power.

Orwell’s rules for writing well have become familiar: don’t use secondhand metaphors, don’t use long words where short ones will do, abbreviate, use the active not the passive, never use a foreign phrase when you can find an everyday alternative in English. They are rules designed to communicate something other than the fact that the speaker is powerful enough to say what he or she likes. Bad or confused metaphor (Orwell has some choice examples of which my favourite is ‘The Fascist octopus has sung its swan song’) presents us with something we can’t visualise; good metaphor makes us more aware, aware in unexpected ways, of what we see or sense. So bad metaphor is about concealing or ignoring; and language that sets out to conceal or ignore and make others ignore is language that wants to shrink the limits of the world to what can be dealt with in the speaker’s terms alone.

But there is something more to be said, which Orwell, a stout enemy of literary modernism, doesn’t quite want to say. In some earlier essays, he had argued that it wouldn’t be the end of the world if literature became less obviously sophisticated, if the range of cultural reference in our writing had to be reduced in order to open it up to more participants. Without quite anticipating the more recent debates about whether there is a real difference between ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture, there is in his work a consistent strand of scepticism about anything that looks like complexity for its own sake, and – as in the famous essay we’ve just been looking at – a feeling that it ought to be possible to say things straightforwardly. And this is where he and Merton might part company. Merton was an enthusiastic modernist in this respect. A good deal of his poetry and some of his prose is written under heavy Joycean influence, and his letters to his old friend, the poet Robert Lax, use a bewildering macaronic style, bursting with puns and allusions and intricate wordplays. It is one of the ways in which he obeys his own injunction to be ‘laborious’. He can even say that, on top of the obligation to write ‘disciplined prose’, a writer has ‘the duty of first writing nonsense…to let loose what is hidden in our depths, to expand rather than to condense prematurely.’

The paradox that Merton is asserting is that in order to be honest the writer sometimes has to be difficult; and the problem facing any writer who acknowledges this is how to distinguish between necessary or salutary difficulty and self-serving obfuscation of the kind both he and Orwell identify as a tool of power. I doubt whether there is a neat answer to this. But I suspect that the essential criterion is to do with whether a writer’s language – ‘straightforward’ or not – invites response. Both Merton and Orwell concentrate on a particular kind of bureaucratic redescription of reality, language that is designed to be no-one’s in particular, the language of countless contemporary manifestos, mission statements and regulatory policies, the language that dominates so much of our public life, from health service to higher education. This is meant to silence response. Nobody talks like that, to quote Jack Lemmon’s immortal comment to Tony Curtis in Some Like it Hot. And so no-one can answer; self-referential power triumphs again. In its more malign forms, this is also the language of commercial interests defending tax evasion in a developing country, or worse, governments dealing with challenges to human rights violations, or worst of all (it’s in all our minds just now) of terrorists who have mastered so effectively the art of saying nothing true or humane as part of their techniques of intimidation. In contrast, the difficulty of good writing is a difficulty meant to make the reader pause and rethink. It insists that the world is larger than the reader thought, and invites the reader to find new ways of speaking. In that sense, properly ‘difficult’ writing is essentially about response: it may in the short term draw attention to its own complexity, but it does so in order that the reader may move away from the text to think about what it is in the world around that prompts such complexity. The final test is whether it makes us see more or less; whether or not it encourages us to ignore.

Orwell might still not be convinced. But I’m not quite sure. In his wonderful essay on Jonathan Swift, ‘Politics vs. Literature’, he resists – a bit more strongly, I think, than he would have done a few years earlier – the idea that a good book must be ‘more or less “progressive” in tendency.’ Swift is a great writer, but not because he is ‘right’: Orwell believes that Swift is unambiguously an enemy who must be fought, because he is ultimately an enemy of the human as we know it. But what Swift does is to take something any intelligent reader can recognise – the sense of futility and revulsion about the physical world and the idiocies and vanities of human agents – and describe the world as if these were the only things of significance in it. Orwell describe this as Swift consciously distorting the world ‘by refusing to see anything…except dirt, folly and wickedness’; and this of course sounds initially like writing that is trying to make the reader see less – just what we have identified as the essence of really bad and poisonous writing. But I think the point is a bit different, and could be phrased in other ways than the ones Orwell uses. Swift knows what we, his readers, all know: that most of the time we don’t want to consider the unacceptable physicality of our lives or the embarrassing vacuity of our individual and social attempts at affirming our moral credentials. So let’s have an imagined world in which these things are made inescapable; not in a way that invites us to deny what we know but in a way that invites us to see what we have been denying; which is something very different from a text that tells us not to see what is there. Swift, like any good writer in Merton’s or Orwell’s framework, is telling us that reality is more than we’d like it to be, and that, if we are trying to be honest, we have to engage with what we don’t like or are afraid of. That invitation may be made by someone whose political or ideological or religious aims are repugnant; but if what he or she writes is recognisable, honesty requires us to keep reading and to admit when the writer’s strategy is well-realised.

And this, I suppose, helps to make sense of Orwell’s conclusion to the essay on Swift – a conclusion that is not as simple as he makes it sound. ‘One can imagine a good book being written by a Catholic, a Communist, a Fascist, a Pacifist, an Anarchist, perhaps by an old-style Liberal or an ordinary Conservative: one cannot imagine a good book being written by a spiritualist, a Buchmanite or a member of the Ku Klux Klan.’ Allowing for the slightly dated references (there are not that many Buchmanites – adherents of Frank Buchman’s ‘Moral Re-Armament’ movement in its original shape – around these days), the argument is still a provocative one. There are systems of belief that are intrinsically not capable of generating serious writing; presumably because they are not really capable of seeing specific truths in a way that can renew or reshape the reader’s world. They may be simply dogmatic schemes without intellectual curiosity; they may be infinitely more lethal varieties of terror and bigotry. They begin with the sort of denials that guarantee dead and self-referring language. They give us nothing to recognise; or perhaps they fail to create in us the sense of a serious question because they are so confident of having a final answer. Orwell grants, in other words, that even a comprehensive ideology like Catholicism or Communism will be arguing about its answers, in ways that engage the outsider: we know why they think these questions matter, even if we have no time for their answers. The trouble with the systems Orwell writes off is that they fail to let us sense why the issues that they are worried about should matter to anyone.

Not a wholly clear argument, but it gives us some interesting criteria, once again, for identifying serious writing. Serious writing points to enough of a common world for disagreement to be worthwhile. Stale ideological writing never moves outside its comfort zone; bureaucratic and pseudo-technical language is indifferent to replies. You can’t disagree; but the systems Orwell thinks are capable of producing something worthwhile are precisely systems that begin with recognisable human questions – not puzzles to which an esoteric philosophy provides solutions but themes that human beings as such characteristically worry about. Interesting that he allows the possibility of a good book being written by a Catholic: only a few months earlier, he had written in an essay on ‘The Prevention of Literature’ that Catholicism ‘seems to have a crushing effect upon certain literary forms, especially the novel’, and asked ‘how many people have been good novelists and good Catholics?’ in the last few centuries. Yet in 1949, he concluded that Evelyn Waugh was ‘abt [sic] as good a novelist as one can be…while holding untenable opinions’. The Swift essay seems to have clarified somewhat his problem with the quality of writing by people holding unacceptable positions, and it would have been good to have the completed essay on Waugh that he was planning in his last months. But the point is of wider application: the relation between politics and literature is increasingly recognised by Orwell as a complex affair. Bad writing is politically poisonous; good writing is politically liberating – and this is true even when that good writing comes from sources that are ideologically hostile to good politics (however defined). The crucial question is whether the writing is directed to making the reader see, feel and know less or more. And the paradox is that, even faced with systems that stifle good writing and honest imagining, the good writer doesn’t respond in kind but goes on trying to fathom what the terrorist and the bigot are saying to makes sense of people who don’t want to make sense of him or her. Failing to do that condemns us to bad writing and bad politics, to the language of total conflict and radical dehumanisation.

Orwell wasn’t all that interested in poetry, and in the essay on ‘The Prevention of Literature’ distinguishes between the way in which poetry might survive in a totalitarian situation where (good) prose would not. But it is clear from his text that he is thinking only of the kind of poetry that is a technically accomplished celebration of public values. He doesn’t seem to think of poetry as necessarily a means of seeing more; Merton’s insistence in his ‘War and the Crisis of Language’ that a poet is ‘most sensitive to the sickness of language’ would not necessarily have found an echo. And Orwell revealingly connects prose writing with post-Reformation ‘rationality’: the essay and the novel, the paradigms of Protestant writing, are what totalitarianism threatens. It is as if poetry is more ‘Catholic’ and so less inherently truthful or critical in Orwell’s world; it can look after itself under Stalinism because what matters in poetry is not the ‘thought’ but the form. Akhmatova, Mandelstam and others might have a view on this. But it is a mark of both Orwell’s consistency and his tone-deafness in certain respects that he makes these curious judgements. For him, what most seriously opposes totalitarianism is the rationality of clear prose. Yet, left to itself, this would be no more than another stipulative definition of ‘reason’; to flesh out the nature of literary resistance to totalitarianism we need a broader account of reason than this, which will allow us to think of poetry as both a challenge to some forms of putative linguistic sanity and a bid for another level of ‘reasonable’ discourse. Merton’s own ground for this is in a sophisticated theology of how the silence of God demands our own silence; and this silence uncovers for us the basic truth that speech itself arises not from the contests of power but from the imparting of life (‘In the beginning was the Word…In him was life’). We do not have to compete with God or one another; the ‘rational’ mode of life in the world of language is exploratory, celebratory, discovering constantly new perspectives – and thus not confined to even the best expository prose. Modernism – Joycean or otherwise – has its unexpected theological place, on the other side of silence.

Whether Orwell might have accepted at least Merton’s conclusion is impossible to say. But the Orwell who so stubbornly resisted the instrumentalising of language for political ends would have fought ultimately on the same side. Uttering the unacceptable in prose and exploring the elusive, not-yet-captured depth of things in poetry have in common the crucial recognition that we shan’t learn about ourselves or our world – including our political world – if we are prevented from hearing things to argue with and things that leave us frustrated and (in every sense) wondering. Our current panics about ‘offence’ are at their best and most generous an acknowledgement of how language can encode and enact power relations (my freedom of ‘offending’ speech may be your humiliation, a confirmation of your exclusion from ordinary public discourse). But at its worst it is a patronising and infantilising worry about protecting individuals from challenge; the inevitable end of that road is a far worse entrenching of unquestionable power, the power of a discourse that is never open to reply. Debates about international issues like Israel and Palestine, or issues of social and personal morals – abortion, gender and sexuality, end of life questions – are regularly shadowed by anxiety, even panic, about what must not be said in public, and also by the sometimes startlingly coercive insistence on the ‘rational’ and canonical status of one perspective only. On both sides of all such debates, there can be a deep unwillingness to have things said or shown that might profoundly challenge someone’s starting assumptions. If there is an answer to this curious contemporary neurosis, it is surely not in the silencing of disagreement but in the education of speech: how is unwelcome truth to be told in ways that do not humiliate or disable? And the answer to that question is inseparable from learning to argue – from the actual practice of open exchange, in the most literal sense ‘civil’ disagreement, the debate appropriate to citizens who have dignity and liberty to discuss their shared world and its organisation and who are able to learn what their words sound like in the difficult business of staying with such a debate as it unfolds. Some years ago, I heard someone describing an event in the Holy Land where women from Israeli and Palestinian communities were being invited to speak with each other. The facilitator began by encouraging the Israelis present not to use the word ‘terrorism’ and the Palestinians not to use the word ‘occupation’. This was not a refusal to admit that both words describe unquestionable realities (or that there comes a time to use those words again); it was an invitation to an experiment in speaking so that response was not foreclosed. I don’t remember whether it worked; but I remember the sense of imaginative challenge: the pain and anger of actual dialogue (that word which is so bland and Pollyannaish as we usually hear it).

Orwell lists the sort of beliefs he thinks provide viewpoints worth arguing with. And one of the things they have in common is that they represent ongoing arguments; they have a history of internal debate. They continue to generate new way of articulating and refining their perspectives. The implication is that good writing comes from a sense of conversation already begun. We never have a world in front of us that has not been talked about and interpreted, and a philosophy that understands and accepts this is one that may be worth listening to. Part of the problem with the language excoriated by Merton and Orwell alike is its aspiration to timelessness; because of course an unquestioned power has no history. Its great claim is that it is natural, obvious, it never has to be learned or tested. One of the most paralysing aspects of any uncritical orthodoxy is a lack of interest in or a positive denial of the process of learning what you believe you know. And it is at this level that an intelligent philosophy or ideology can move beyond sheer self-assertion and self-reference. Once we acknowledge that we speak as individuals who always have a location in time as well as space, we are that much freer to assume that our current language is still moving forward or outward. This certainly doesn’t mean an irresistible historical trajectory towards consensus or towards a weakening of distinctive commitments; but it at least allows that what can be said at any one moment is unlikely to capture everything that could or should be said. And if so, there is going to be some space in even the most comprehensive and ambitious of the philosophies Orwell lists for the work of the imagination, for making the world strange again. What both our authors are worried about in ‘late modernity’ could be expressed as a fear of the world being made strange – a fear common to murderous totalitarianisms and to the ‘timeless’ managerial culture of so many contemporary institutions. You don’t have to think that the one is as bad as the other to recognise that there is an uncomfortable convergence in this nervousness about language that doesn’t behave appropriately, language that suggests there may after all be a reply waiting to be made.

Of all the various lessons to be learned from Merton and Orwell as analysts of linguistic decadence, the most obvious is that literature and drama are not a luxury in society. Politics can’t avoid the drift towards the twin abysses of totalitarianism and triviality if it refuses to face the perils of this decadence. Good writing is many things. For Orwell it is primarily to do with the capacity for reasoned prose and the sustained personal narratives of classical fiction. For Merton, it includes some wilder elements, the freedom for wordplay and the absurd, as well as poetic experimentation. But it is always writing that declines to close down either perception or argument. This is how good writing defends us from absolute power or – which comes to much the same thing – absolute social stasis. It leaves a trail to be followed and asks questions that require an answer: it pushes towards a future. This obviously doesn’t mean – recalling Orwell’s observation – that good writing is ‘progressive’; only that it is aware of being between past and future, living in time. And Merton, with another theological twist that Orwell would probably not have much appreciated, also implies that if our fundamental human problem is ‘Prometheanism’, wanting to steal divinity from God rather than labouring at being human, then good writing, with its inbuilt ironies and its awareness of its own conditions, is one of the things that stops us imagining we are more than human.

Perhaps that’s as good a definition of good writing as we’re going to find. Destructive politics is inevitably bound up with forgetfulness of our humanity, in one way or another – the organised inhumanity of tyranny, the messianic aspirations of Communism, the passion for control on the part of managerial modernity, the naked and brutal murderousness of terrorism. But Merton explicitly and Orwell implicitly remind us that this is not just about bad governance or oppression. If we talk and write badly, dishonestly, unanswerably, what we are actually doing is getting ready for war. The habits of mind that make war inevitable are the habits of bad language – that is to say, the habits that grow from uncritical attitudes to power and privilege: contempt towards the powerless, towards minorities, towards the stranger, the longing for an end to human complexity and difference. Orwell explicitly and (perhaps) Merton implicitly are trying to identify the all-important possibility that we may passionately quarrel, even that we may fight to defend ourselves against political evil in one way or another, without simply buying in to various kinds of totalitarianism, overt or covert. Orwell has an almost mediaeval sense of what is involved in battling to the death to defend yourself against an enemy for whom you retain a degree of simply human respect, in that you do not seek to dehumanise them, to put them once and for all outside the boundaries of human discourse and exchange.

However we pursue that fight (not exactly an academic question today; and Orwell and Merton would disagree sharply here, I think, given Merton’s near-pacifism), the central moral question is whether we are going to use the language of tautology and self-justification, the language that gives us alone the right to be called reasonable and human, or whether we labour to discover other ways of speaking and imagining. If we settle for the former, we are already planning the next round of violence. The latter is hard and counter-intuitive because it does not promise what we most of us secretly long for, a simple end to conflict and complication. But it is the very opposite of resignation, because it summons the writer to work, to the constant creation and re-creation of an authentically shared culture – the pattern of free and civil exchange that is neither bland nor violent. The ‘small blue capsule of indignation’ has to be punctured again and again. And if Merton is right, that means the writer needs rather more than just ideas; she or he needs something of the contemplative liberty to sift out the motivation towards bad writing that comes from the terrors and ambitions of the ego, and find the liberty to allow words to arrive both fresh and puzzling. Easy to imagine Orwell’s raised eyebrows at the thought of his contemplative vocation; but if this brief attempt at staging an encounter between these two passionate and contentious writers has come anywhere near the truth, that’s what might have to be said about the calling not only of Orwell but of any writer worth reading.

Dr Rowan Williams, former Archbishop of Canterbury, gave the 2015 Orwell Lecture on 17th November 2015, at University College London.