Local journalism isn’t all about traffic accidents, who got sent to prison this week or the opening of a supermarket chain. Across the country, local journalists play a key role in informing communities, holding powerful people and institutions to account and highlighting inspiring stories or voices.

YOU CAN ALSO DOWNLOAD A PRINTABLE PDF VERSION OF THIS RESOURCE HERE.

But, along with the journalism sector as a whole, it has suffered from a crisis in financial sustainability, that has led to a downturn in the quality and availability. Highlighting its importance, research has shown that good local journalism helps strengthen democracy and communities.

But, along with the journalism sector as a whole, it has suffered from a crisis in financial sustainability, that has led to a downturn in the quality and availability. Highlighting its importance, research has shown that good local journalism helps strengthen democracy and communities.

A positive sign is the growth of local journalism projects that are aimed at restoring trust and reaching diverse communities with a focus on quality journalism and community engagement.

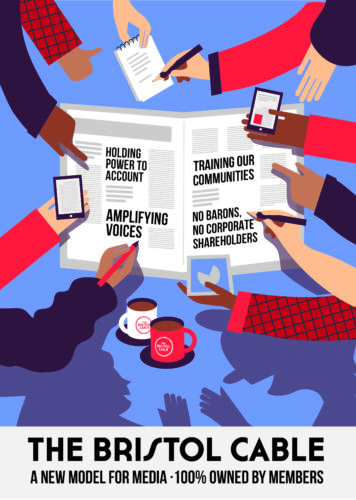

The Bristol Cable is a leading example of this new movement for a better media. Launched from a living room in 2014, the Cable is 100% owned by 2,300 members (and counting) who all have an equal share. We produce award winning local journalism in print and online, free to access for all, and pioneer new methods of reaching and engaging communities, through events, training and democratic participation. Find out more here.

This resource, produced by the Bristol Cable, is designed to get you started with some key concepts and tips for creating local journalism that is exciting, engaging and hard hitting.

Types of stories:

There are different categories for journalistic work, and there is a debate on how best to categorise or label them. But broadly, much of journalism can be broken down into the following:

News reports

These will generally be factual updates on events as they unfold. However, publications will take a different tone or approach depending on their editorial leanings. For example, the Times is generally more conservative while the Guardian is generally more liberal.

Example: The council are now opposed to Bristol Airport expansion despite previous support. But what does that mean for the plans? (Bristol Cable)

Academy plan to change admissions rules could ‘displace’ kids (Liverpool Echo)

Opinion or voice piece

These pieces are written in the first person, meaning the author writes about their own experiences, thoughts and opinions about a specific topic or issue. This is often aimed at making a specific argument in the case of an opinion piece, or telling a personal and powerful story, in the case of a voice piece.

Voice example: Vulnerability, escapism and creativity, my experiences of lockdown as a young Bristolian

Opinion example: ‘We must not let Bristol’s coronavirus recovery be built on shortsighted banks, empty gestures and missed opportunities’

Features journalism

This is a catch all category for more creative and colourful writing, that encompasses interviews, essays, longer pieces with more context and multiple sections.

Example: Meet the Bristol collective putting surplus wealth in the hands of people tackling injustice

Example: Bristol filmmaker Michael Jenkins is ‘wreaking the best kind of havoc on the city’

Investigative journalism

This form of journalism is usually aimed at exposing or revealing something that isn’t already known about and that maybe controversial. This is an area that has legal and ethical risks, and demands special skills and knowledge that should only be undertaken with the support of an experienced journalist.

Example: Finally exposed: How Lopresti ice cream boss kept men in slave-like conditions, tenants and families in squalor. But people spoke out. (This series of stories was shortlisted for the Orwell Prize for Exposing Britain’s Social Evils 2020)

‘Broken people in a broken system, Manchester’s forgotten families’, Jennifer Williams, Manchester Evening News. (This piece by Jennifer Williams, Investigations Editor at Manchester Evening News was part of a series longlisted for the Orwell Prize for Exposing Britain’s Social Evils 2020)

For the Orwell Youth Prize, the best approach is an opinion, voice or feature piece where you can touch on big issues in a creative and personalised way.

So how to go about that?

Building a strong story:

Depending on what sort of story or topic you are working on, different aspects will be more or less important.

However, there are some key elements to think about and combine to make a powerful story

Local is global:

We live in a massively interconnected world, where incidents or issues happening across the globe can affect us, directly or indirectly. By using local examples of stories that help shed light on a national or global issue, we can tell stories that may feel unconnected to us in a way that brings it right back to our doorstep and can make people sit up and take notice.

For example, maybe there is a refugee family living on your street who’s experience of their homeland and now living in the UK can help tell the story of conflict, migration and Britain today. Or perhaps, someone you know is spending a lot of time on social media. How does this connect to the power and influence of global mega-corporations like Facebook or TikTok?

Facts + Humans are a powerful combo:

Facts are the building blocks of journalism, and making sure that the facts we publish are accurate is a crucial responsibility of a journalist. However, having a compelling human story that helps illustrates things like data and statistics is a great way to help the general public be interested and engaged.

For example, we know that thousands of people are facing eviction due to problems paying rent as a result of the coronavirus. Can you give any personal experience or speak to a tenant who is in this position?

Connecting on the emotional level really helps to bring statistics to life. Asking yourself the question ‘why should someone care?’ can help you help you not get buried information and keep to what’s important to convey the story.

Examples: ‘Most families find it shameful’ – Finding pride in a community where being gay is taboo

Context, context, context

Arguably a weakness of much of journalism is that it tells us ‘what is happening’, but not ‘why’. By exploring and explaining ‘why’ we can help the reader have a greater understanding of this sometimes bewildering world we live in! One technique is to delve back further into the past to help explain an event or development by looking at the factors or history of the issue.

Obviously it’s important to acknowledge that there’s often different views or opinions on why something is happening. Make sure to be clear when an opinion is being stated (including your own!), rather than an agreed fact.

Examples: Vox Explainers

Dig deeper

One of the first places a journalist will begin research is through a search engine like Google, an amazingly powerful tool. However, often the top results are news articles. Try digging a bit deeper by researching the sources, people and information cited in the news to get some more detail and a better feel for the topic. It can sometimes feel a bit overwhelming because of how much information is out there, but try to organise your notes in a document, and save links you want to follow up later on. It’s all part of getting immersed in a topic!

Examples: ‘Bristol Water is trying to hike your bills and ‘tip the scales in investors’ favour’

And finally, it’s not all doom and gloom

There’s an old saying in journalism that “if it bleeds, it leads”, meaning that news organisations put the grimmest stories front and centre. No doubt, it’s necessary to highlight the bad and the ugly around us, but this can often lead to sensationalist headlines designed to anger and shock people. However, there is growing evidence that a constant barrage of negative news is prompting people to switch off and disengage with what’s happening all together. As a response there is an emerging trend of ‘solutions journalism’ that explores and highlights campaigns, technological breakthroughs, inspiring community projects and big ideas that can help us both understand and begin to address the challenges we all face.

Examples: Big ideas of what a good ‘new normal’ could look like after coronavirus

See more solutions journalism here and here.

Things to think about:

Privacy, people’s stories and the ‘right to reply’

Journalists have the right to ask questions and approach people to speak to them. However, individuals, particularly in private situations or regarding sensitive matters, also have the right to decline to speak. It’s important to respect people’s privacy and ask for consent to interview them, for example.

A journalist should be independent of people they interview. But at the same time, if you are telling other people’s intimate stories, check in with them about what elements you are going to focus on and seek their feedback. Remember that you are the author, but also that you should be sensitive to their concerns.

Different rules apply if you are making a factual allegation against someone or a company, for example. You must give them the opportunity to respond to the allegations, in what is known as a ‘right of reply’. However for the purposes of the Orwell Youth Prize you should steer clear of stories that may raise these complicated editorial and legal issues without the advice of an experienced journalist.

Fake news:

As the saying goes: “A lie can travel around the world and back again while the truth is lacing up its boots.” While not all fake or inaccurate news is spread maliciously, it can be hard to spot and may be shared in your social circles. A key skill of a journalist is to question things, so if you see something online or IRL, you can do your own research to work out if it’s accurate.

Some resources for fact checking and fake news:

Headlines:

‘You’ll never guess what this chimpanzee does next?!” is a classic example of a clickbait headline. Though the chimpanzee probably does something amazing, headlines should aim to give the reader an idea of what they are looking at, while at the same time enticing them to read your piece. It can be a tricky balance, is a question of style and is an art in itself. You can test out different versions with people you know. What would make them click on the link or read the story?

Getting started:

Now you have a better understanding about concepts and top tips for journalism, you’re ready to get started. Think about the following questions as a checklist:

- What is the big issue or topic that I’m thinking about?

- What original or interesting perspective or ‘angle’ can I give?

- What information do I need to gather or people do I need to speak to?

- What sort of story-type will I go for?

- What is the deadline and word count?

Glossary:

Explanations of some of the trickier terms within this resource:

Financial sustainability: The ability to be financially stable and continue to cover costs and invest in the organisation

Democracy: There are different types of democracies and the systems can be complex and some are more democratic than others. All involve some form of right to elect governments and other officials for all citizens, as well protections such as a fair and independent legal system, a free press and other rights such as joining a trade union and freedom of expression.

Media co-operative: A media organisation owned democratically and equally by many individuals, rather than single owners or corporate investors

Why should I pick reporting/journalism as the genre for my Orwell Youth Prize entry?

The Orwell Youth Prize is interested in your viewpoint on what is happening in your area. How do things happening around you relate to national and global problems? What can your perspective or the perspective of those you know add to the issue? We want to encourage you to try it out,

Good reporting requires research, rigour and clarity. It may be outside your writing comfort zone, but when done well it can have a big impact. One of our 2020 winners Jessica Tunks is a great example of this. Following her win, Jessica’s piece ‘Knifepoint’ has been republished in VICE and on the Scottish Violence Reduction unit website. The piece also provoked comment from her local MP Stella Creasy:

“In 1984 Orwell wrote ‘They can’t get inside you if you can feel that staying human is worthwhile, even when it can’t have any result whatever, you’ve beaten them’. This piece embodies that spirit; it holds a mirror to our community and speaks fearlessly and clearly about how pathways for young people like Ali become cut off, as society fails to value their future and our shared responsibility in that process. To write with such passion about knife crime and its impact is to be a voice that makes a difference; someone who isn’t beaten by injustice but is using their platform to call for us all to address it. In doing so, ‘Knifepoint’ embodies the relationship Orwell described so powerfully between independence of mind and changing the world.” Stella Creasy, MP for Walthamstow.